Early Modern England, Yale History MOOC with Keith E. Wrightson

Notes and excerpts from 'Early Modern England', a Yale History MOOC with Keith E. Wrightson.

I took this course from December 2nd 2022 to January 1st 2023. I watched through the whole playlist but did not read (nor did I have access to, I think) the supplementary material or handouts. All in all a great resource, which gave me a better picture of what early modern English society and culture looked like. I especially enjoyed the more general lectures about society at large, more than those focused on successions of events. The Elizabethan era with its intricate plots and intelligence, and the Glorious Revolution with a crash course on how to form a functioning Republic were amazing. I like seeing the story of how sometimes, even if unfrequently, centrists actually succeed.

Demographics (Lecture 2)

England in the 1520s had ~2.4M people. 2% were nobles (peers and gentry, who lived off rents), <10% lived in towns, <5% in towns with >5000 inhabitants. Commons could be yeomen (substantial tenant farmers), freeholders or husbandmen (with enough land to support their family, but relying on family labor), tradesmen and craftsmen (ale brewers to smiths), and cottagers or laborers who lived off wages, though complete dependence on wages for survival was uncommon.

About 25% of the population were servants, and they made up about 60% of the population between the ages of 14 and 25. In 1550, 10% of the population were apprentices. They kept the same master for the whole period of study (about 7 years), enjoyed a superior status than servants.

Households (Lecture 3)

Huswifery was about managing the consumption needs of the household: mending clothes and cooking. Women were forbidden from trades, even baking, but they sometimes participated informally.

The first child was typically born after 18 months, followed by another every 2-3 years for about 30% of a woman’s life. Big random events that shaped and destroyed lives included bad harvests (perhaps once every 5 years) or epidemics (mostly bubonic, and potentially killing 20-30% of the population once every 10 years).

Marriages were not simply arranged, except for the aristocracy, but parents were happy to present candidates. Young people were permitted a considerable degree of choice among eligible and acceptable partners.

Key Institutions and Relationships (Lecture 4)

In this period, England was a myriad of small settlements (badly mapped initially), governed by noblemen and landlords in the shape of manors or parishes.

Relationships between neighbors were extremely important at this point in history. There was a more communal way of looking at life, with an emphasis on ‘neighborliness’. Each parish had a community, and people were interrelated by family ties, economic ties and a shared religion. The other side of this was a huge amount of obligations between neighbors: they would borrow each other money and favors, and there would be strong pressure from all sides on people to act as society expected of them. Distant relatives also tended to help each other and serve as contacts, for instance when looking for an apprenticeship for a son.

People tried to maintain their credit: their reputation as being trust-worthy and such.

Towns had a sense of identity as autonomous, self-governing communities. Something like a third of inhabitants would be fremen, able to participate in the town Politics. Citizenship was contingent on being part of a guild, by being master of a trade and having finished one’s apprenticeship.

Guilds laid business regulation on matters pertaining to the guild’s trade, and kept people from outside the guild from practicing it. They also acted as mutual aid societies.

York had 64 guilds, carlisle 8. Being a guild member made you a citizen and you could then participate in civic life (non-members who tried to practice the craft were kept out). Guilds controled business practices, labor relationships with apprentices, etc.

Law was based in custom, where what was customary dictated the possible uses of land and such (like current Common Law, based on precedent). They would bring the oldest people in the village to opine on legal matters when there was a dispute, so they could consult their experience (and their memory of precedent).

Social and Economic Networks and the Urban System (Lecture 5)

Babergh Hundred. Richmond.

People from different villages would all coordinate to travel to the closest town on market day. Different towns would do market day on different days, so the same village would visit a different town every time. This cross polination led to people meeting each other (and so marrying outside of their village), and economic activity.

Though the economy was mostly Agrarian, each region tended to also practice different trades and have varied exports. London and York excelled in elaborate trades (and trading luxury goods), Sheffield was known for its knives. The south east mostly tended crops, whereas the North and Wales specialized in sheep and goats. Bristol was a significant port in the West, and rivers connected different cities accelerating commerce. Norwich was known for its fabrics, which would ship to Antwerp from London.

These interconnections were especially important for the elite, though common folk also experienced their effects.

Late Medieval Religion and Its Critics (Lecture 7)

The Clergy comprised about 4% of the English population, and therefore close to 8% of the male one. People gave 10% of their income to the church as tithes. The Church in England was the biggest organization after the government.

Parishioners donated more in tithes (for the beautification and refurnishing of their churches) than they paid in taxes and contributions to their lords. They formed guilds or religious fraternities, to maintain altars and pray for the souls of the members of the guild and their families, besides contributing to charities.

The Church judged and applied laws in some regards, particularly those pertaining marriage, inheritances and other ‘spiritual’ affairs. This raised contempt from common lawyers.

Reformation and Division (Lecture 8)

Under Henry VIII, who fought the Pope legally to get his marriage annulled, England migrated to a idiosyncratic form of Catholicism which put the King at the center of decision-making. Without officially changing doctrine, Parliament dissolved most of the smallest monasteries and printed a vernacular bible in English, which was actually translated unofficially by Protestants.

After Henry XVIII’s death, his son Edward was much more openly Protestant and his advisors also leaned towards protestantism, accelerating reform and solidifying Protestant doctrine. By 1553 the Church had become clearly Protestant.

After Edward’s early death, Mary daughter of Henry and Katherine, a Catholic, took the throne. She was a Catholic and got England back under the Pope, married the King of Spain (with reluctant support from Parliament) and started persecution of unrepentant Protestants, including burning them at the stake. She died in 1558, making her reign quite short.

Economic and Social Problems, 1520-1560 (Lecture 9)

From 1500 to 1550 England dealt with unprecedented inflation. Sticky rent prices put a pressure on the nobility, who reacted by enforcing “enclosures”, where common land was fenced and appropriated by noblemen, who could then charge rents. The new supply of land brought about by the confiscation of Monastic land by the Crown was mostly gobbled by noblemen as well, especially highborns who were not firsborns and could with this transaction become landed gentry.

The yeomen became more powerful as they were not subject to (or as influenced by) rising rents, and their crops were rising in value thanks to inflation. Landholding leases went from 90 year periods to closer to 10 so that amounts could be adjusted.

This sparked two peasant revolts (the gracious revolt and the one in Kent) and eventually parliament tried to address inflation and stagnant wages with new economic policies (indeed the earliest forms of political economy were being established). In the 1560s Parliament passed the statute of Artificers and established a poor-relief system (the levying of the ‘poor rate’ and its dispersal) in parishes across the realm.

Religion in the times of Queen Elizabeth (Lecture 10)

Under Queen Elizabeth I, religion became again an idiosyncratic mix of Protestantism and Catholicism, after she passed her initial agreement, the Settlement of 1559.

- Papal authority was abrogated.

- Priests were allowed to preach and read the prayer book as they chose in practice, but had to officially subscribe to Protestantism.

- The dogma was officially Protestant.

It was mostly an attempt to keep the peace.

In 1568, while Mary, Queen of the Scots, was kept in house arrest by the Queen (she was a Catholic, her direct cousin and a claimant to the English throne), the Dutch Revolt happened.

Spanish troops were stationed under Philip II in the coast of the Netherlands, and Catholics in England started smuggling priests and even Jesuits, plus some revolts took place. They multiple times tried to depose Liz I, put Mary in the throne and marry her to the Duke of Norfolk (a crypto-Catholic) until he was killed.

There was at first a 12 pence fine -about 1 day salary for a journaler- for not attending the Church once a month, and it was raised 400-fold after the conflict escalated in the 1580s. In 1585 England entered open war with Spain and supported the Dutch provinces. This is where the Spanish Armada happened (they failed to cross the narrow sea and got scattered trying to get back to Spain).

In 1586 Mary was executed after the Babington plot.

Religion-wise, in the latter half of the 16th century the ‘hotter sort of protestants’ emerge: Puritans and so on, bent on further reformation. They would congregate in ‘prophesyings’ and discuss clerical matters even with the laymen. As the first generation of Elizabethean bishops died in the ~1580s, a new archbishop was named who was a Calvinist.

The Elizabethan “Monarchical Republic” (Lecture 11)

Due in part to the Queen being a woman, and in part to the rising power of the emerging sectors of society.

She is a central figure in English history as she reigned for 45 years and defined much of the culture and so on. She governed with a privy council which defined many policies (those she did not regard as under her direct purvue, unlike religion and foreign policy). She chose to postpone any decision on succession until the end of her reign was near, to the dismay of Parliament who decided not to pass any laws until she would declare an heir. She also never married, choosing probably to postpone that too.

Elizabeth was crowned in 1558, and formed her council thereafter. The most important and famous member of the council was William Cecil. An older man, a bureaucrat and a strategist with a habit of writing copious notes. Her councilors had ideas about the monarchy that put it below the will of the people, unlike the typical absolutist view where God Himself apoints a King/Queen and their powers flow from there. “It is not her who ruleth, but the law” and so on. She would insist that her councilors would not dare say something like that about her father.

In foreign policy, the Queen tried to act as little as possible, to avoid any irreversible actions. As allies with Spain they were at war with France, and France sought to maybe annex Scotland and then England through Mary’s claim. She supported the Lords of the Congregation, the Protestant lords of Scotland who eventually took the throne and educated James VI (and I of England), son of Mary when she was imprisoned in London after the Treaty of Edinburgh. In 1585 England intervened for the Dutch in their war for independence, reluctantly at first. Mary was sentenced to death after the Babington plot, but the Queen sought to withhold the execution order and not apply it. However her men carried it out anyways.

In the 1590s the war in the Netherlands continued, and drained the English reserves. There was also an insurrection in Ireland, unsuccessful, fanned by the Spanish. She died in 1603, leaving the throne to James I (and VI), with the monarchy now a subdued institution compared to that of the times of Henry VIII.

Economic Expansion and Social Polarization (Lectures 12 and 13)

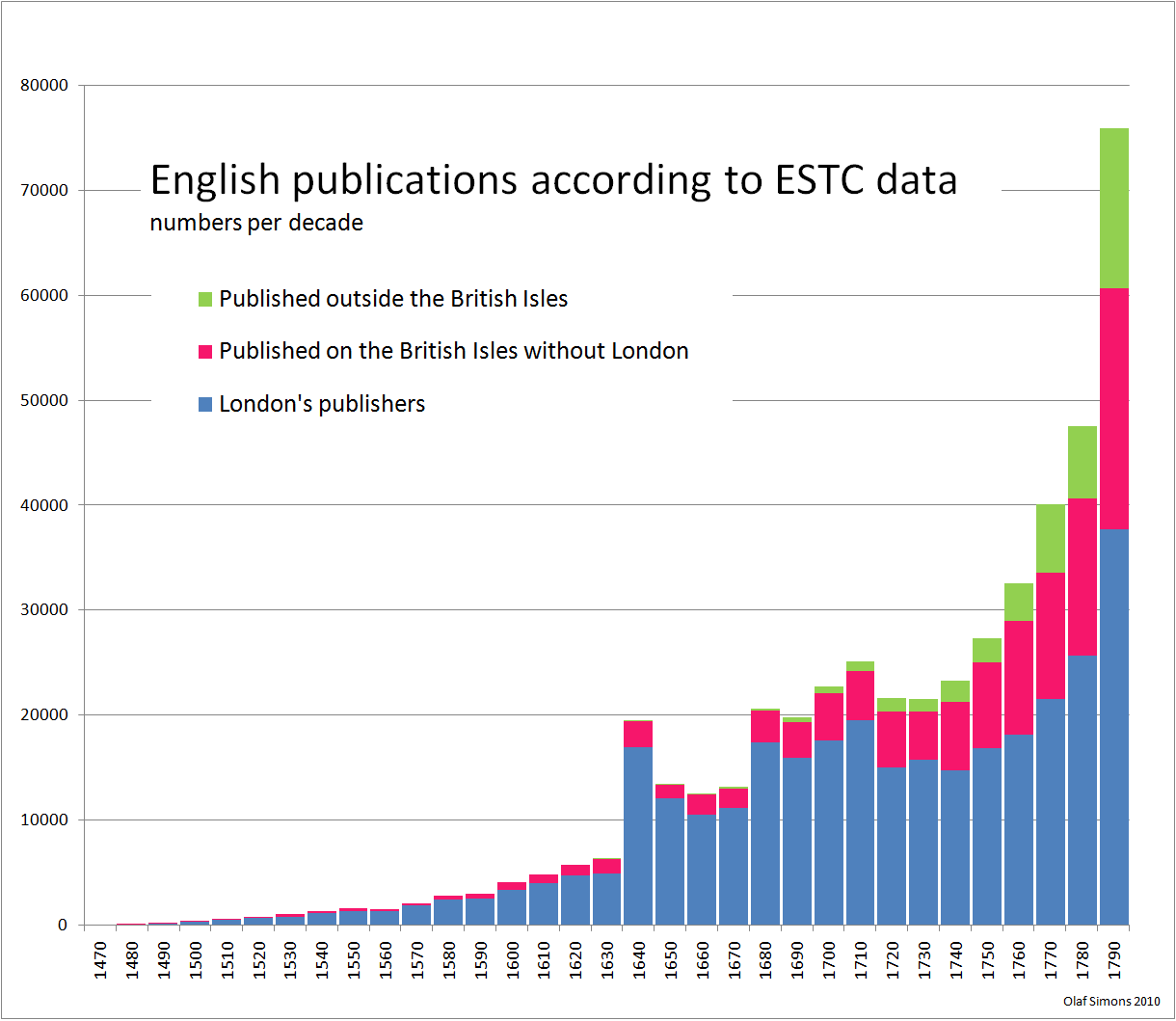

The English population exploded between 1550 and 1700, especially that of London. It doubled or tripled depending on the region. The economy grew to sustain such a population growth: crop yields increased, enclosures (first by lords on community land, then to divide the land for individual holders) became widespread, first unpopularly but then much more normalized, and inflation was rampant for the first time (at about 3% yearly).

People did not have the capacity to understand macroeconomics then, nor to see the inflation, but the reduction of real wages was aparent to all. Land rents increased significantly and leases grew shorter, which increased tensions between the Gentry and the common folk. Yeomen became more powerful as they had more surplus to sell and crop prices increased, whereas most peasants, especially the young, became unable to buy or rent land and had to resort to working as journalers their whole lives. Less people married, too.

The population urbanized a lot more –London grew a lot, and the other cities usually doubled their population, though the top 5 combined weren’t as big as London alone.

Industry also expanded, with new kinds of finished clothes now produced locally rather than imported from the Netherlands. Other guilds also appeared, and the Crown created many chartered companies: monopolies that were initially very profitable and helped in industrialization by substitution of imports. They produced things like glass, pins and clothes. Metallurgy, mining and others expanded greatly. Some of these chartered companies found new trade routes and brought new luxury items to London, like the Levant company that brought rugs and a different one which would become the East India Trading Company.

The use of coal served to heat most homes in London using less land than if wood had been used instead, freeing up more land for agriculture. Many forests were brought down to make cultivable land.

Internal trade grew in significance, through roads and rivers. New commercial practices also brought a huge new class of lawyers and traders.

The pauperization of the rural populations led to increased tensions, in big part because of the already mentioned rising rents. In the second half of the 16th century Parliament passed the Poor Laws to alleviate this, and in a typical parish only about 20% of people would contribute to the relief system, and another 20% would be benefitted by it.

Witches and Witchcraft (Lecture 14)

A great lecture, not gonna make lots of notes of it. The biggest things that drew my attention were:

- There was no torture in England, unlike in Scotland or Continental Europe, which helps to explain why there were no massive, widespread accusations of witchcraft.

- England had laws against witchcraft but the Justices of the Peace refused to enforce them and lawyers were reticent to present charges or participate in such trials, due to the difficulty of procuring evidence.

- Essex was the only place with a great share of the Witchcraft trials, probably due to very publicized ones in the beginning of the mania.

Crime and the Law (Lecture 15)

For violent crimes, during the 16th and 17th century we see them decrease, from homicide rates at about 3x the modern England rates to much less by 1600. Homicides tended to be between neighbors, and mostly a case of aggravated assault meets lack of penicillin. Unlike in current times, murder between family members was rarer. The exceptions would be closer to the border, where gangs of thieves and organized criminals would go on raids with crossbow, pony, sword and cudgels, and steal cattle in great quantities while killing people.

Theft and property crimes rose with the economic hardships of the 16th and early 17th centuries, and were divided in capital and petty theft. The line was 1 shilling (12 pence) - a day’s wages. Capital theft was punished with death, petty theft with whipping. Men did 85% of the thieving. There are predictable rises in theft when there were bad crop years.

Judges exercised discretion and mercy by reducing the reported value of the stolen goods, or allowing clergy to non-clergimen and even illiterate people: all criminals needed do was memorize the verse. Even so, people were hanged for crimes at about 150x the rate of, e.g., 2020 Texas.

Popular Protest (Lecture 16)

Rogation Day: the oldest members of the village and the youngest boys would walk around the boundaries of the parish and demarcate them.

Protest took many forms, most often tearing up fences from enclosures, or breaking dams and remaking swamps in the Fenlands after drainage (Cromwell was famous for having defended fen restorers in Parliament).

Though defined as riots at the time (for a riot was any crime perpetrated by 3 or more people), the protests were often pre-announced, and targeted, with almost surely no casualties or injured people, only material damage.

There was often an emphasis in the restoration of customs, as per common law.

Education and Literacy (Lecture 17)

The population at the beginning of the 16th century was not uneducated, but unschooled, as school participation rates were around 10%; this reserved for lawyers, the clergy adn certain trades (like tradesmen who would need to learn foreign languages).

By the beginning of the 17th century this had greatly changed. There were two big driving forces for this:

- Renassaince Humanism: Not centered in secular values, but in combining Christianity with reading the ancient classics, to form an educated aristocracy. Models of education emerge that sound very foreign to current ears e.g., learn Latin from 7 to 14, Greek from 14 to 17, then read Plato and study Ethics and Philosophy, plus horsemanship, dancing and the military arts.

- Protestantism: Educate the clergy and even the laymen, as it was important that people could read the Bible and for clergymen to be able to explain theology and answer questions, as well as educate the public at large.

This extends the education from the elite to the general population. The 16th century saw a transition from private tutors at home to grammar schools and then heading to Cambridge or Oxford.

In the 1620s gentleman students could buy multiple books, with one example cited who bought about 10 books in 2 years.

By 1563 26% members of parliament had attended university. By 1642, 50% had.

In the mid to late 16th century, funded by clergymen, merchants and gentlemen usually from London, a plethora of grammar schools were founded, to the point where for instance Lancashire had one on every town. Education here was mostly classical. They taught the 4 r’s: reading, ‘riting, ‘rithmetic and religion.

By the early 17th century most towns had a grammar schools and many villages had a petty school (which only taught literacy and basic arithmetic).

Most who attended university were sons of noblemen, or of the richest sort of merchants or professionals, as they were very costly. The same happened with grammar schools, but petty schools did penetrate most of society.

By 1642 (Protestation Oath) 30% were literate, and towns were much more literate than villages. In the 1660s it was common enough for people to read that commoners would be reading chapbooks and almanacs (hundreds of thousands were printed each year).

Puritans and Arminians (Lecture 18)

The Puritans were the ‘hotter sort of Protestant’, usually opposing episcopality or centralization of the church and advocating for a decentralized, bottom-up religion where people would gather and discuss scripture directly.

The Arminians defended a more centralized and traditional way of Protestantism, with an emphasis in the Sacraments as opposed to rigorous interpretation of scripture, giving for instance the communion a bigger importance (albeit without transubstantiation, of course). They would have remained an obscure sect were it not because Charles I decided to join them. They were seen as a return to popery and absolutism by their opponents, including Puritans, and they slowly but surely overtook England’s religious institutions, as Charles I used his power to appoint them as bishops, ending with the appointment of the Bishop of Westminster himself.

Crown and Political Nation, 1604-1640 (Lecture 19)

James I started his reign with an optimistic welcome and a well formed consensus. Though there were pressures between the hereditary privilage of Parliament and the will of the monarch, they were not exceeding of what was typical for the system.

This changed in the 1620s. A combination of political, economic and social factors including foreign policy.

The Duke of Buckingham, the favorite of James I, was eager to exert power, and generated controversy while controling royal patronage, with all that that meant. He grew hated due to his incompetence in matters of state and his favored position. This combined wiht an unstable foreign policy situation with the 30 years war (which began in 1618) where the king’s son in law was deposed.

There were 5 parliaments between 1621 and 1629, infrequently many. There were quarrels over whether England should participate in the 30 years war, anxiously watched by the English elite.

In 1526 Parliament met to provide money for the war (England had joined on the side of France, after Charles I married the princess Henrietta). Parliament refused to provide funds if their Protestation was not accepted. The Protestation was a protest against Buckingham and the Arminian bishops. The King dissolved parliament to halt the impeachment of the Duke, but got no money. Then he proceeded to tax the gentry using ‘prerogative power’ and Buckingham declared war against France as well as Spain, to help French Protestants, but his campaign failed and squandered money.

In 1628 Parliament was called again, to raise money. The Commons promised to vote a bill of funding if the grievances about the forced loan and Buckingham were heard, and the Petition of Right were signed.

The Petition of Right said:

- No taxation without Parliamentary consent

- No arrest of subjects

- No billeting of troops without subjects’ consent.

In August of 1628 Buckingham was assassinated.

In the late 1620s there was a functional political breakdown in the consensus system. Conflicts in society included Arminianism, Buckingham and his campaigns, the King’s taxation without Parliamentary approval and the behavior of troops.

There was talk among parliamentarians about a poperist conspiracy that aimed for absolutism and taking the power of Parliament. The other band spoke of the popular spirits, radicals who wanted to encroach on the Crown’s rights: crypto-Presbyterians, or Puritans.

In the 1630s the King declared peace and started levying taxes of questionable legality (some based on medieval precedent). The 1630s seemed really calm, but there was also no place for public protest.

In 1637 the King and Archbishop Laud tried to impose an English style prayer book and the episcopal church on Scotland. This insistence on uniformity had catastrophic blowback. Their reform looked ‘popish, atheistical and English’.

Constitutional Revolution and Civil War, 1640-1646 (Lecture 20)

This topic is much more deeply discussed in the related article: The Restless Republic my notes for a book concerning this period.

In 1639, after about a decade of coasting through peaceful times, King Charles I faced a problem. He tried to convert Scotland to Arminianism, which Presbyterian Scotland didn’t like one bit.

The King summoned Parliament to procure funds for defense, and these were unprecedentedly contested elections (25% of seats were contested). That was called the Short Parliament, because the commencement speech was cut short before 3 minutes had passed when the King dissolved it. The speech was a condemnation of the King’s actions.

Then he summoned a new Parliament after Scotland invaded and took over the North of the realm. The Scots were more experienced in battle as they had fought in the 30 years war and the Dutch wars of independence.

These elections were even more contested at about 30%, with close to 30% of England’s male adult population voting.

That parliament finally read the grievances from all the kingdom and got the King to back down in some Arminian reformations, and executed members of the privy council. They passed the Tertiary act (which made it mandatory for Parliament to convene at least once in three years) and removed the right from the King to dissolve parliaments.

In 1641, after news of the rebellion in Ireland (a nationalist, Catholic uprising of Irish chieftains and the Old English of Norman medieval ascent) and the massacres in the North (populated mostly by the planted Scots), John Pym passed (narrowly) the Grand Remonstrance.

- Parliament should have the right to choose the King’s councilors.

- An assembly of divines should convene to decide the religious future of the kingdom.

This act divided parliament, and the King declared against it and used it as a way of getting supporters. He tried a coup in 1642 by storming parliament with the army.

This same year, Parliament gave itself the right to raise an army (through ordinance) and made an offer to the King called the Nineteen Propositions –more extreme than the Grand Remonstrance in the rights conferred to Parliament. Parliament and King each raised an army and fought.

A fifth of all adult males fought in the war. Most of the Aristocracy fought for the King, 2/3rds of the House of Lords. Most of the middle-sort fought for Parliament.

Parliamentary (roundhead) forces were concentrated in the south east and controlled London. They sought to stall and press so the King would come to terms. Royalist forces encroached from the West and the North and sought to take London and its whereabouts to negotiate with a defeated Parliament.

Parliament was divided between those for peace (to negotiate favorable terms) and those for War (to keep pushing). War faction, led by John Pym, allied with the Scots through a covenant, getting their military support in exchange for reform of the church of England (to make it Presbyterian).

In 1644 the Scots attacked from the North and besieged York. Prince Rupert son of Charles tried to drive them away but was met by Cromwell’s army who defeated him (with famously disciplined cavalrymen) gaining renown.

By 1640 the censorship of the press had stopped, and new religious groups were emerging. In 1645 the Parliament army, led by Cromwell, defeated the main Royalist armies.

Regicide and Republic, 1647-1660 (Lecture 21)

This topic is much more deeply discussed in the related article: The Restless Republic my notes for a book concerning this period.

After the war was lost, the King was kept under arrest by the Scots and stalled while Parliament offered him a set of terms. These terms included presbyterianism and a pardon for all who fought in the war, plus the execution of about 50 noblemen who fought on his side.

He stalled and the Model Army of Parliament, controlled by Lambert, carried him by force to London, where their supporters in Parliament (mostly independents or Puritans) drafted a new set of terms: the Heads of the Proposals. These were much more convenient for the King: most of his men would be pardoned, the army would be controlled by Parliament for 10 years (as oposed to the 20 the previous terms offered) and Parliament would meet every 2 years. The King stalled.

The Levellers inspired the army to take the Agreement of the People after much debating. It included writing down adn simplifying the laws, expanding suffrage, and more proposals.

The King escaped and obtained the right to receive visitors in the Isle of Wight. Here he plotted with his Scottish supporters, and made the Engagement. The engagers from Scotland invaded England, and English and Irish supporters organized uprisings and began the war anew in 1648. This was the second civil war, and it hardened the hearts of the army. They beat him again, including the Scottish army, much larger than Cromwell’s.

Disillusioned that the king was still king, Colonel Thomas Pride conducted his Purge: he only let 150 members of Parliament enter the chamber and vote, limiting to those who shared the army’s view. They tried the King, under decision of the House of Commons without the assent of the House of Lords, and executed him.

This small parliament governed as it could under the Republic, and the army was focused on taking down Ireland and the Covenant army. At this point the north of Ireland was taken by British landowners who ruled their lands, creating the conflict that continues somewhat to this day.

By 1653 the Commonwealth was created. With peace, tensions emerged. The only reform so far had been the Act of Toleration and a small simplifying of the laws, but nothing like the Puritans or the Levellers expected.

In that year, Cromwell took over in a coup and controlled the country for five years. First he appointed a Parliament of selected ‘godly’ men. This failed and dissolved itself -after some religious reform like the abolition of tithes-, after which the Republic under the Instrument of Government was created.

The republic -the Protectorate- was based on the Heads of the Proposals, but the new Parliament that was elected immediately began to attack the Lord Protector, religious toleration and the system. In 1657 he was offered the Humble Petition, where he would take the crown and the ancient constitution would be restored.

Cromwell was seen as a regicide by his opponents, and something of a tsundere ruler by his ex allies (“it’s not like god wants me to smite you, b-baka”). He died in 1658 and was the only one who could hold every faction together. The Rump was restored after his inadequate son was brought down. General George Monck intervened from Scotland and restored authority. First the Rump, then all survivors of the Long Parliament of 1640.

In 1660 Parliament dissolved itself and called for new elections. Charles II appealed from exile and wrote the Declaration of Breda.

- Respect the liberties of Parliament.

- Pardon everyone who fought against him.

- Liberty of conscience.

An Unsettled Settlement: The Restoration Era, 1660-1688 (Lecture 22)

The Restoration effort was planned and executed by the Earl of Clarendon, Charles II chief minister. It included recognizing all laws and reforms up to 1641 (before the Heads) including the Triennial Act and

- Recovering confiscated Royal land

- Recovering confiscated Church of England land

- Pardoning anyone who fought in the war (general act of indemnity and oblivion) excepting only the surviving regicides.

Subsequent reform was mostly favorable to the King, like abolishing freedom of the press.

The Calavier Parliament was reticent to grant Freedom of Conscience. The Act of Uniformity was passed, banning all clergymen who were not of the Church of England from even living close to towns. Something like 10% of the population were dissidents (no longer only Puritans, but also Quakers and the like).

The King signed an agreement of cooperation -Treaty of Dover- with the French stipulating that they would ally with them against the Dutch, even though the Dutch were very popular amongst the English political nation. It had two secret clauses were the French would pay the King a pension and also he would eventually convert to Catholicism and proclaim liberty of conscience including dissidents and Catholics.

Thus began the 2nd and third wars with the Dutch, which were not as successful as the first (led by Cromwell, where they were victorious). Parliament forbid Catholics from taking office -Test Act- and married Mary, niece of Charles II (who had no heirs and had a Catholic brother) to William of Orange. foreshadowing.

Funnily enough this time there was an actual conspiracy to establish popery and absolutism in England.

In 1679 the Exclusion Parliament, which aimed to exclude James (brother of Charles II) from succession, was elected. This after the Popish Plot scandal and the leaking of the secret clauses of the treaty of Dover. The King opposed exclusion and Parliament was dissolved, and the Licensing Act which had expired was not renewed, so freedom of the press was back, bringing a deluge of pamphlets.

The political nation divided into Tories and Whigs. Whigs were for exclusion and against popery and absolutism (they would burn pope effigies in processions). Tories were on the side of the King and would frequently remind people of the breakdown of ‘41 as a warning not to rock the boat.

The Exclusion Crisis came as Parliament convened and was dissolved again when pushing for exclusion, and the King chose not to call for a new one, started dissolving the charters of cities which had Whig inclinations (I didn’t quite get how this mechanism worked exactly), and persecuting dissidents (especially quakers) throughout the 1680s. The nation was politically highly polarized.

The King then died at his most powerful, and converted to Catholicism in his deathbed.

James II was closer to Charles I in temperament, whereas Charles II resembled James I more. He undermined his own position with his deeply sincere catholicism.

He filled the Kingdom and authority positions with Catholics (judges of the peace, even the Irish governor). He passed a Declaration of Indulgence, suspending penal laws against dissenters and Catholics. His actions had been clearly illegal. He tried to repeal the Test Act and got very unpopular. In 1687 it was revealed that Queen Mary was pregnant, so he may have an heir. He also made every parish read the Declaration of Indulgence, and declared the seven biggest bishops traitors when they opposed this.

The public rejoiced when they were absolved by the courts, and then prince James, James II’s heir, was born. In 1688 this proved too much and the ‘Seven Immortals’, leading political figures including the Earl of Danby, sent a letter to William of Orange inviting him to take the crown and secure a free Parliament, while investigating the birth of James’s son. William of Orange proclaimed that he would “preserve the Laws, Liberties and Customs of England”.

The King fled and was allowed to escape to France, and in 1688 an assembly of the nobility asked William and Mary to take the reins of government.

England, Britain, and the World: Economic Development, 1660-1720 (Lecture 23)

The Glorious Revolution brought massive changes in the structure of government and Britain’s standing in the world.

Throughout the 17th and early 18th century, population remained almost constant. Fertility went down and did not recover until 1760. Life expectancy was 33 even after the last plague in 1666, due to background mortality. Also emigration to America in the latter half of the 17th century, and internal towards London which had a lower life expectancy due to transmissible disease.

Factors in this period were:

- Population stabilization.

- Diminishing cost of food (mostly grain).

- Growing real wage for craftsmen and laborers.

There was regional specialization in agriculture, and processes became more efficient with the diffusion of innovation. There was also great urbanization: total population remained nearly constant but rural went from 60% to 40%.

Many towns and cities grew enormously besides London, leading to diversification of the economy. The main export, woolen cloth, went from 92% share to 70%.

Imports also grew, mostly in luxury goods like silk, wine and woods. Pepper, tobacco and other commodities from the Americas and the East grew too. A great deal of these imported goods, rather than being consumed domestically, were exported to other European markets.

Complex overseas trade emerged, especially in the triangular format. This was incentivized with protectionist measures like forcing ships to stop in England or forcing trades to be conducted only with British ships. Standardized manufacture grew incentivized by the bulk selling (production remained under the ‘putting out system’).

Surplus income was destined to the ‘decencies’ of life: neither luxury nor necessity, like forks (invented around this time).

In the second half of the 17th century coal mining grew and was sold locally for heating and industrial processes. This trade led to the invention of the steam engine (to drain water from coal mines) and wooden wagon rails for coal wagons. Some of these undertakings were the biggest civil engineering projects undertaking since the Romans had left.

Each region specialized in a certain trade (cloth, coal, etc.) and towns were central in concentrating production in each place. Coastal traffic and river passes grew enormously, and roads were also improved. At this point in time, early 18th century, village shops emerge.

Refashioning the State, 1688-1714 (Lecture 24)

The Glorious Revolution brought King William III (of Orange) to power. He was married to Queen Mary, the first daughter of James II.

Parliament passed a centrist Settlement with the support of both Whigs and Tories, that included things like freedom of religion (all religions could be practiced privately, even Judaism. All brands of Protestantism could be practiced publicly), and limited the powers of the King (Parliament must convene every three years and could not be dissolved, for instance).

In the following decades the fiscal-military state apparatus emerged. Greatly incentivized by the war in Continental Europe (against France in the war of succession, mostly) and the war against the Jacobites (who tried to bring James II to the throne again, and then Jamess the would-be third or pretender, his son), Parliament devised multiple ways to increase public revenue. Taxation became more thorough and broadened greatly (especially Land Tax and then excises), as Parliament managed to give the King an allowance but keep control of public revenue. As trust in public revenue uses grew, Parliament began to devise and control multiple mechanisms for securing funding, mostly around public debt. The Bank of England was created as were different kinds of bonds (including lottery bonds). My notes on this so-called financial revolution continue in Ascent of Money: Book Notes. The interest of this public debt (which amounted to 10% of total national income) owuld be paid for with tax revenues.

Related reading: How the Dutch Did it Better, Anton Howes

Parliament began to be called once a year, out of necessity as there was no other way of securing funding. Not an intended aspect but a welcome one of the new system. Royal ministers, though appointed by the monarch, still needed to be approved by Parliament or their projects would not get funded. At this point Parliament really divided into two parties Tories and Whigs. This polarization permeated every aspect of society in cities and towns, and more elections beacme contested. By now Parliament was not only called once a year but also elected every three years.

In 1701 the Act of Settlement was passed (for the further limitation of the crown and better securing of the rights of the subject). It fixed the succession on Sofia of Hanover, solely because she was the next protestant successor. It also forbid them from marrying Catholics or being Catholics. The Crown also lost the power to appoint or remove judges at will.

This is why after Queen Anne died, she was succeeded by George I, Sophia’s first son.

Most of Scotland supported the Revolution as it was governed by Protestant Whigs. Close to 13% of the population died in famines in the 1690s. Their industry was not as developed as the English one and they were excluded from English colonial trade, while also unable to secure their own colonies.

In the end, Scotland and England negotiated a Union: Scotland would recognize the Act of Settlement (and the Hanoverian succession) in exchange for England providing them access to the colonial markets and other economic concessions. The Treaty of Union was signed in 1707, forming the United Kingdom of Great Britain. Scotland joined the English Parliament, but retained church and legal independence. Scots were granted full access to English trade, their taxes would be reduced and their industries protected.